Tannic Panic! Issue #94: Yeast The Friendly Beast

Today, we take a closer look at some of the "science" behind wine’s little buddy: "yeast"

You ever wonder how wine, a “beverage” made from the juice of the humble grape, can produce so many diverse styles? How is it that one type of fruit can produce the aromas and flavors of wildly different fruits, and also flowers and bread and nuts and earth?

Yeast may be the culprit.

Yeast is the cornerstone of winemaking, transforming grape juice into wine through a process we all “know and love” — fermentation (THE GOOD KIND!).

TLDR; fermentation: sugar + yeast = alcohol + CO2

But yeast also contributes significantly to the wine's flavor profile and overall character, owing to both the “ingenuity of man” and the great diversity of yeast strains that exist on “mother earth.” (MOMMA, CAN YOU HEAR ME?)

The primary strain of yeast used in winemaking fermentation is Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is favored for its predictable fermentation capabilities, tolerance to high alcohol levels, and ability to thrive in normal wine pH conditions, but there are countless others, and many of them have unique qualities that contribute differently to the wines they interact with.

To understand how it all fits together, first it’s important to understand the different ways different types of yeast sneak their merry little way into the winemaking process.

TYPES OF YEAST IN WINEMAKING

In winemaking, there are two main categories of yeast: wild (or indigenous) and commercial yeast strains.

Wild yeasts exist in nature and are introduced to the wine from the grape skins or the winery “environment” itself, potentially enhancing complexity and expressing regional characteristics that can give wines a distinctive sense of place. But like nature, they can be unpredictable, and relying on wild yeasts can carry risks, like off-flavors, stalled fermentations, and overpopulation of undesirable strains.

DID YOU KNOW… Some yeasts are just generally considered pests, leading to off-flavors, excessive VA, and potential spoilage or balance issues in wine due to their ability to ferment residual sugars even at high alcohol levels. These “naughty” yeast strains include such household names as: Zygosaccharomyces bailii (click for pronunciation), Hanseniaspora spp., Wickerhamomyces anomalus, Saccharomycodes ludwigii, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and Torulaspora delbrueckii.

But not all are simply bad. Certain wild yeasts can negatively or positively influence wine characteristics depending on the quantity and personal preferences. A classic example is Brettanomyces (aka “Brett”), which when present in small amounts can add complexity with earth, band-aid, or leathery notes, and is part of the signature style in numerous old world regions (e.g., Bordeaux, Rhone, Barolo, etc). Higher concentrations, however, can lead to off-flavors described as "barnyard" or "horse sweat," and may also produce excessive volatile acidity (THE BAD KIND!).

And of course, many wild yeast strains that influence regional styles contribute their own appealing characteristics. Hanseniaspora uvarum, for example, which is common in Southern France, can impart aromatic fruity characteristics. Metschnikowia pulcherrima, abundant in Poland, offers spicy and floral notes. The list goes on and on.

Commercial yeasts, on the other hand — primarily Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains — offer more control and consistency in the fermentation process. With countless commercially available “options,” winemakers can choose strains suited to different wine styles and grape varieties. It allows for the fine tuning of fermentation temperatures, speeds, alcohol levels, pH, and so on, as different strains have different levels of tolerance to varying environmental conditions.

Commercial yeast strains can also be selected to impart specific flavors like spice, earth, fruits, flowers, etc., or to enhance particular characteristics already present in the wines. The metabolic activity of certain yeast strains can also influence non-volatile components like tannins and anthocyanins, impacting the wine's astringency and color (opacity).

These wonderful little examples illustrate how yeast strain selection alone can significantly shape wine style outcomes, affecting both aromatic and structural elements in the finished wine.

WILD VS. COMMERCIAL - “THE GREAT DEBATE”

While the debate between using wild or commercial yeast often centers on the balance between authenticity and control, the decision to use wild or commercial yeast ultimately depends on the winemaker's goals, the grape variety, and the specific conditions of each vintage.

Wild yeasts may produce more expressive, terroir-driven wines, but they can be less reliable and more challenging to work with. Commercial yeasts offer consistency and predictability but may result in wines that some perceive as less unique or expressive of their origin.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in wild ferments among winemakers and consumers alike. This trend reflects a desire for wines that showcase the unique characteristics of their terroir and possess a sense of authenticity with minimal intervention.

CASE STUDY: RIDGE VINEYARDS

A notable example of a winery committed to natural yeast fermentation is Ridge Vineyards in California. Ridge uses a "pre-industrial" approach, fermenting their wines with native yeasts from the vineyard rather than cultured strains. This method aligns with their minimal intervention philosophy and belief that natural yeasts produce more complex and interesting wines that reflect the terroir of the vineyard. For their flagship Monte Bello Cabernet Sauvignon, grapes are hand-harvested by parcel and whole-berry fermented with native yeasts, followed by natural malolactic fermentation. While acknowledging the risks, Ridge believes this approach leads to wines that better express their unique terroir and possess interesting characteristics unattainable with commercial yeasts. This approach seems to be “working quite well” for Ridge, as we’ve rarely ever had a wine from them that wasn’t somewhere on the spectrum from very good to outstanding in quality.

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

Well that’s all good and well, but a question that is inevitably EATING AWAY AT YOUR MIND faster than RFK’s brain worm collection, is why the heck does yeast contribute all of these crazy different flavors and aromas to wine? What business does a humble microscopic fungus have smelling like sunshine and raindrops? Well, to jump in on that, here’s a little guest blurb from our dad, who’s also “a scientist.”

Patrick Brown on yeast, insects, evolution & terroir

Yeast can’t walk or fly (LIKE ME!). They survive and grow when they have sugary liquids to feed on (like fruit or a drop of tree sap). But when they’ve exhausted the available food (for example, when the fallen grape is completely fermented and there’s no sugar left), they need to get to another food source, or eventually DIE.

So how do they get to their next meal…?

They need to hitch a ride on the flies or bees or wasps or other flying insects that are attracted to fruit (or flowers that will eventually produce a fruit), which means that they need a way of attracting those insects themselves. For that reason, there’s a strong natural selection for the yeasts’ ability to synthesize volatile compounds that have fruity or floral aromas.

Wine yeasts (most, but not all, are strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae) commonly have specialized metabolic pathways that produce “secondary metabolites” (compounds not essential for normal metabolism, but often involved in attracting, repelling, killing or changing the behavior of other organisms of the same or different species, like flower aromas or colorful pigments that attract pollinators, pheromones, natural antibiotics like penicillin, other toxins, bitter compounds to deter predators, etc).

For yeast, the aromatic compounds that attract insects (and wine lovers) are typically synthesized in response to starvation (i.e., in the late stages of fermentation, when they’ve fermented all the sugar, and they desperately need a lift to their next meal). Since it increases the yeast’s odds of survival for the insect to deliver them to a fruit or a flower, it’s advantageous for many of these secondary metabolites to smell fruity or floral. Of course, some of the yeast and other microbes that wind up in wine fermentation might also thrive in dumpsters or rotting leaves, so there are yeast and other microbes that produce aromas that are not fruity or floral (and sometimes downright nasty), attracting insects that will make a beeline (or a fly line) to the nearest dumpster.

The part of this spiel that’s about evolution and the “purpose” of the secondary metabolites is speculative. But it’s a fact that yeast produce secondary metabolites that are often fruity or floral (and often other interesting) aroma compounds, especially when they’re starving. And it’s a fact that different yeast strains produce different constellations of compounds, resulting in different flavor and aroma compounds in the wines they contribute to fermenting.

My favorite theory for “terroir” is that a big contributing factor is the local ecosystem of the vineyard - the wasp and bee and other flying insect species that live in and near the vineyard and have nests nearby that year after year harbor the native yeasts that contribute to the characteristic flavors and aromas of the local vineyard, then are attracted to broken grapes and inoculate them with the yeasts they like. The local flowers, fruits and other potential food sources in the vicinity might also be part of the system, since they help define flying insects are resident in the vicinity and what aromas those insects are attracted to, and therefore what yeast secondary metabolites will be most effective in attracting a flight to the yeast’s next meal.”

YEAST AUTOLYSIS & LEES AGING

Before we dive into our measly set of reviews this week, we can’t leave out one other crucial (and relevant to this week’s reviews) way that yeast contributes to wine’s distinctive flavors and aromas: yeast autolysis.

Yeast autolysis is the process by which yeast cells break themselves down through the action of their own enzymes. This typically occurs when fermentation has been completed, and as it occurs the dead yeast cells (known as “lees” in the world of wine) that remain in contact with the wine begin to impart a new array of flavors and textural characteristics to the wine.

It is a hallmark of certain styles, like traditional method wines (e.g., Champagne, Cava, Franciacorta, etc), where lees aging in the bottle is used to imbue flavors and aromas of toast, brioche, cheese, and nuts, and can give the wine a richer mouthfeel. It is also famously used in “sur lie” wines, like those commonly found in the Loire.

Anyway, before we get too caught in the lees here (*CRINGE*) let’s dive into the juice!

… AND NOW FOR THE REVIEWS (IN ORDER OF PRICE):

[CLICK HERE FOR A BREAKDOWN OF HOW OUR 100PT RATING SYSTEM WORKS]

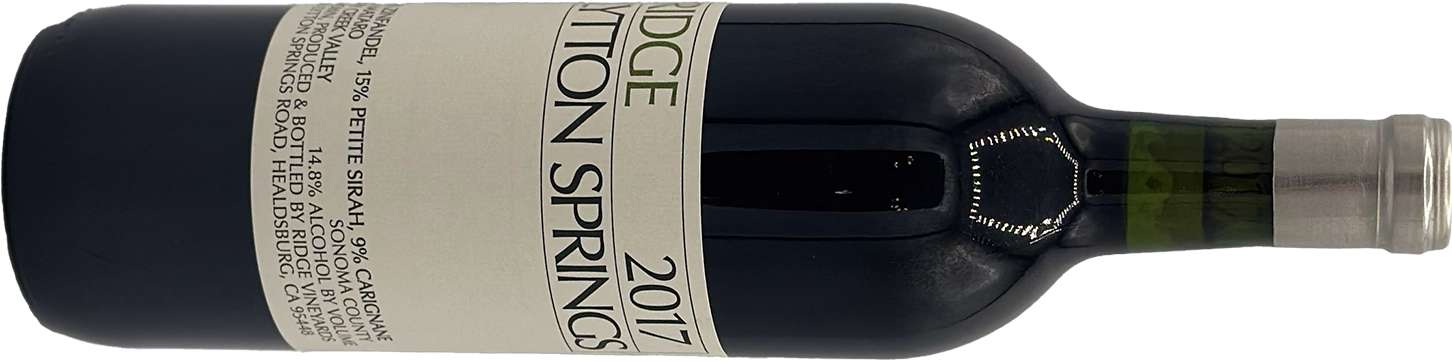

2017 Ridge Lytton Springs

Profile: Black plum, black cherry, blackberry, dried strawberry, mixed spice, leather, chocolate, orange peel, rose petals, clove, black pepper

Palate: Dry, full body, medium+ tannin, high acid, long finishBlend: 74% Zinfandel, 15% Petite Sirah, 9% Carignane, 2% Mataro

This wine showcases a beautiful blend of black and red fruits, floral notes, spicy elements and some tertiary complexities from bottle aging. Unlike many other California Zinfandel-led blends, which are typically jammy, often teetering into “off dry” territory and unstructured, this is a clear outlier, as it’s bone dry with good tannic structure and acidity. Kudos to the “wild yeasts” that reside on the grapes in this wonderful little “field blend.”

Score Breakdown: Balance 36 / Aroma/Flavor 17 / Concentration 15 / Length 15 / Complexity 8 = 91 Points (Z)

Albert LeBrun Grand Cru Champagne

Profile: Brioche, almond, toast, fennel root, lemon peel, baked apple, wet stone

Palate: Dry, high acid, medium body, long finishGreat value in the Grand Cru Champagne category with great balance with classic Champagne character. Dominated by brioche and almond notes, this is a perfect illustration of how yeast can impart flavors post-fermentation through lees contact. The autolytic notes are rounded out by lemon peel and baked apple, and some earthy floral notes, like white clover flower (IF I REMEMBER CORRECTLY FROM CHILDHOOD WHAT THAT SMELLS LIKE) or perhaps fennel root. Easy drinking with a long finish. Hell yeah.

Score Breakdown: Balance 37 / Aroma/Flavor 17 / Concentration 15 / Length 15 / Complexity 7 = 91 Points (I)

Yeast, that sneaky little rascal that contributes so much to the wines we all love.

Where would we be without it? Who knows.

So now it’s your turn — any thoughts, questions, or insults about our writing that just can’t wait? Serve em up in the comments!

Until next time, HAPPY DRINKING PEOPLE.

Cheers!

Isaac & Zach

One of the craziest yeast stories I just researched - one of the de-alc sparkling wines I'm gearing up to taste test claimed they were the only ones in the world who used a *secondary fermentation* in the bottle like a champagne, to correct a lot of the lost flavors and aromatics during the de-alc process.

Naturally, this made me scratch my head - wouldn't that just lead to the need to de-alc the wine all over again?!? Turns out no - they found a handful of yeast strains that ferment additional sugars when added to the bottle (again, just like in chanpagne) but produce *minimal alcohol levels*. So little, that the final juice remains at a level they can still call fully non-alcoholic!

That blew my mind. Yeasts are...well...wild.

Well I never! I knew there were commercial yeasts and wild yeasts, but honestly I had no idea how they actually impart flavours to the wine... Can't think of anything witty or insulting to say - just thanks!