Tannic Panic! Issue #135: Wine Spectator's Top 10 Has a Type

A critical look at the flaws and biases underpinning Wine Spectator’s annual “Top 10” list

Every year, “influencers” (UNLIKE ME!) around the globe think it’s a cute idea to “evaluate” Wine Spectator’s “Top 10 Wines of the Year” and share their “2 cents” on the “results.”

Our approach here is a little different. As enthusiastic consumers of Zeus juice, there are so many options out there that vetted lists of wines (especially with a mind for value and availability) are highly useful tools for today’s “thirsty youth” (and who doesn’t love a nice little “list”?).

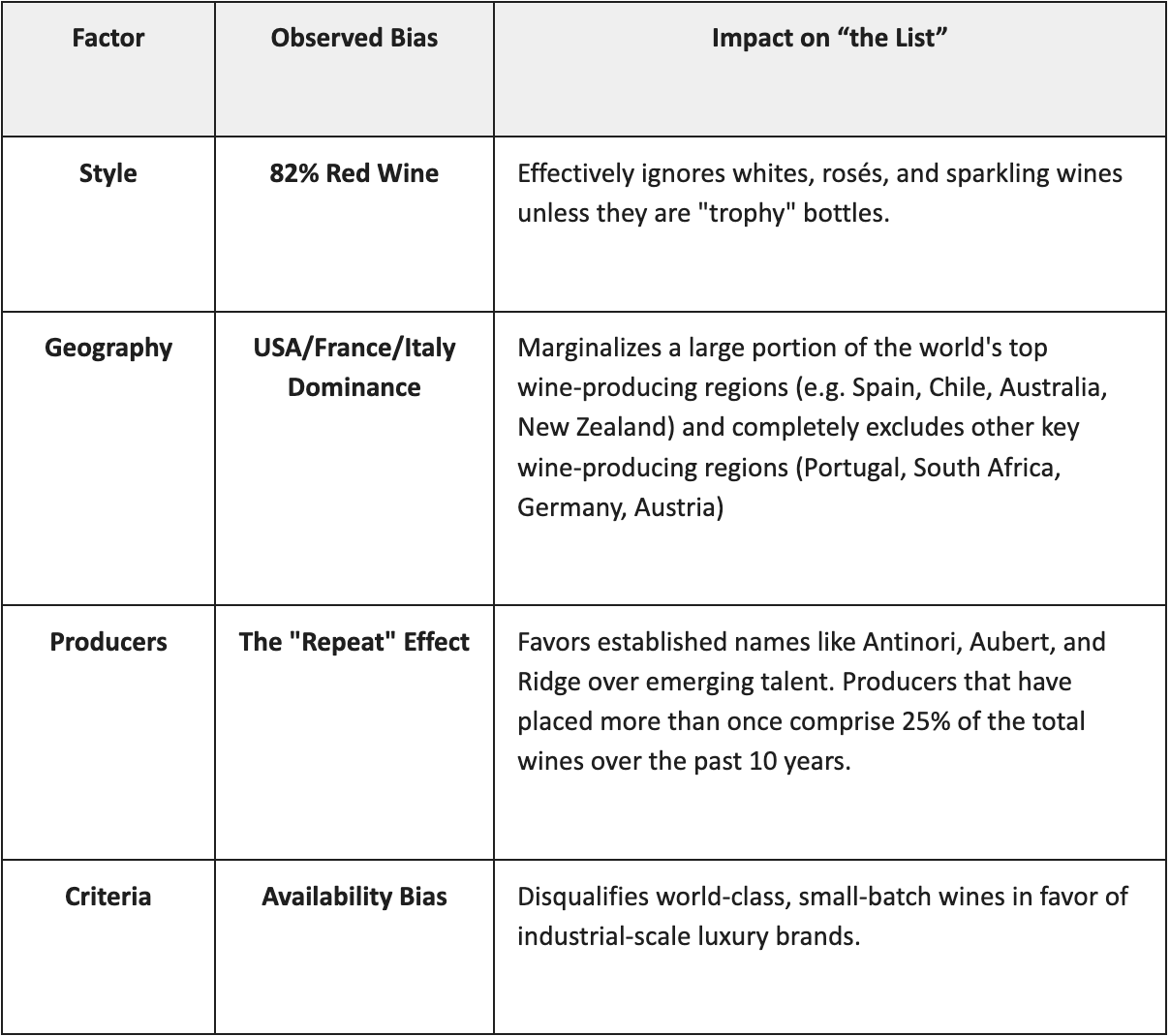

We aren’t so much questioning whether the wines that made the list are “worthy” of praise, or even top of class — We’re questioning whether we’re actually looking at a selection that’s even remotely objective when deciding which wines are in the running.

The problem with a list that declares wines to be “the best,” especially coming from a major wine publication like Wine Spectator, is that people will naturally assume that these wines have been pitted against the rest of the options they have available, and subsequently deemed superior. The reality is that a huge number of worthy “contenders” are disregarded by design, and when you look at the data, even applying their stated criteria as objectively as possible, there is further evidence of bias toward specific countries/regions, styles and even the humble “producers.”

This week, we’re getting a little more “numbery” than usual, with some “neat little graphs and charts” that break this all down in terms “we” can all understand.

Let’s take a gander at the selection criteria for the list:

Wine Spectator’s Top 10 comes from all wines they blind‑taste in a year, narrowed first to those scoring at least 90 points, then to the Top 100, and finally to 10 wines that ~allegedly~ best fit their little criteria. It’s among the additional criteria that we see inherent bias that misleads when deeming these wines the “best” of the year.

Four core factors allegedly drive the Top 10 choices:

Quality: Only 90+ point wines qualify; within those, higher scores and standout character, balance, and typicity are favored.

Value: They look for wines that “overdeliver” for the price, focusing on price–quality relationship, not just low cost.

Availability: Preference goes to wines made or imported into the U.S. in sufficient quantities so readers can realistically find them.

“X‑factor:” An added element of “excitement” or “story” (e.g., a benchmark vintage, a breakthrough producer, or a wine that represents an “important” trend.)

Here’s the results from 2025:

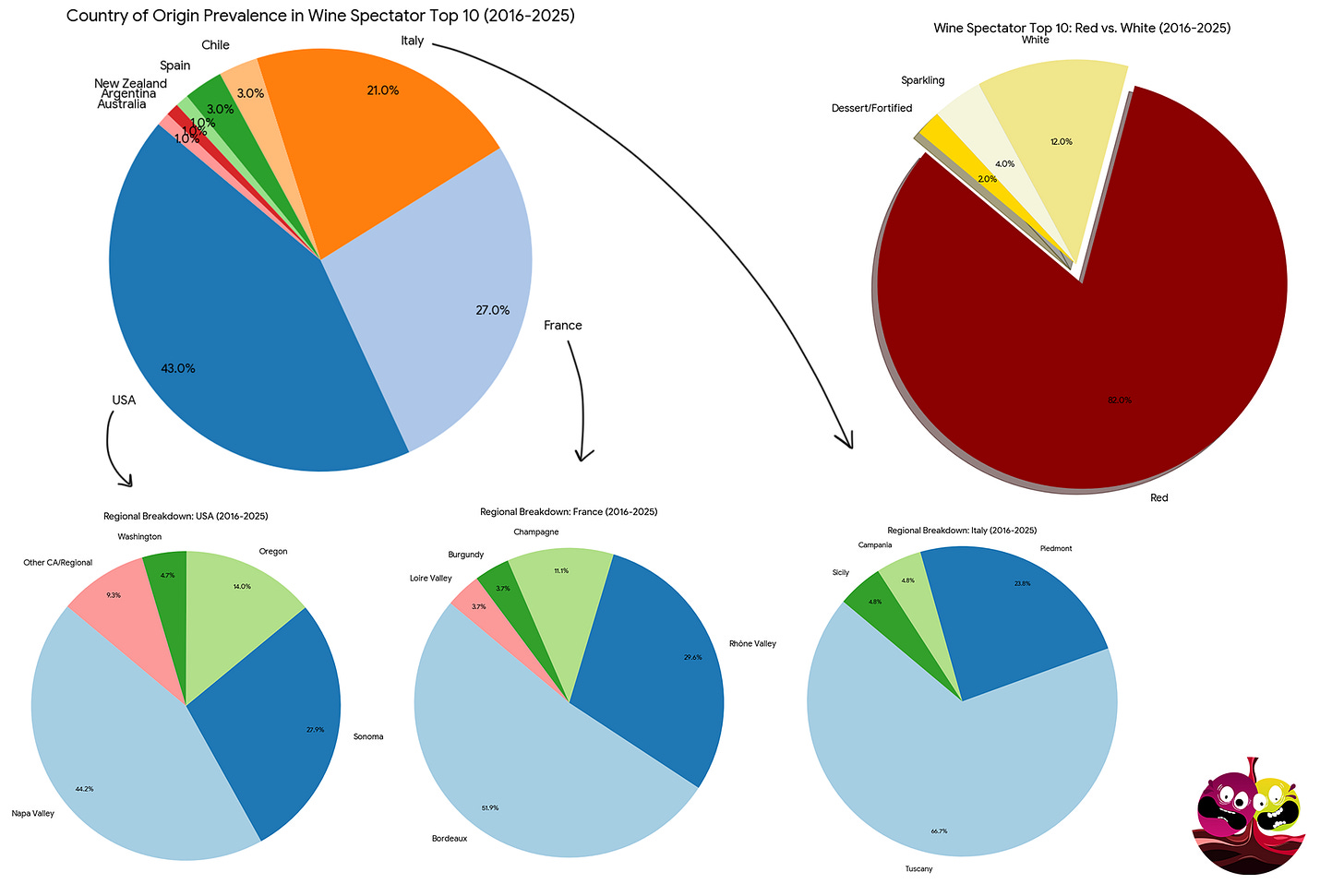

Note that only USA, France and Italy dominate the list, with 1 wine from Chile thrown in “for optics.” Historical trends tell a similar story, with USA, France and Italy dominating the top 10 lists for the past decade, followed distantly by Spain, Chile, Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. No other countries are represented at all.

We won’t get too deep into it in this post, but we would be remiss if we didn’t also point out that the relationship between ranking, price, and the WS score out of 100 is hard to make sense of. For example, the 2023 Ridge Lytton Springs is the cheapest wine on the list (according to WS) and scores the same (95 points) as the #1 ranked 2022 Chateau Giscours, yet it ranks #3. While the Ridge is slightly lower total production volume, it is also more widely available in the US. Similarly, the 2022 Chateau Beau-Séjour Bécot is 15% cheaper* than the #2 ranked 2023 Aubert Chardonnay and has the same score (96 points), yet it ranks #5 (*based on the WS listed price of $100 for the Aubert, not the actual average price on the public market which is closer to $300; wildly misrepresenting price is a common trend on the list). Not only that, but the Aubert Chardonnay is far more difficult to procure — the vast majority of it is by allocation, meaning that even if it were the same price and score, availability would presumably have pushed this one lower in the rankings 🤔. This casts doubt on either the list, the system they use for scoring or both. If anyone wants to break down the “logic” on that for us, please do so in the comments.

Anyway…

Here’s a look at the outcomes for the past 10 years, visualized in “charts”:

Let’s “talk” about these “results”

The data from 2016–2025 underscores a WONDERFUL little structural bias toward red wines and a specific “Power Trio” of regions: Napa Valley, Bordeaux, and Tuscany. While white wines and “diverse” regions like Spain or Australia make up a massive portion of the American wine aisle, they are largely sidelined in the Top 10 rankings. For instance, Spanish Ribera del Duero represents incredible value in the red wines under $30 price category and are very well distributed to the USA. Yet it has appeared exactly 0 times in the past 10 years — and Spanish wines barely made an appearance. Other major wine countries like Portugal and South Africa are completely absent. This isn’t just a reflection of quality, but a byproduct of Wine Spectator’s criteria, and evidence of bias that goes beyond it. By prioritizing wines that are widely imported and possess a certain prestige, the list naturally gravitates toward large-scale, “high-scoring” producers in “established” regions which creates a self-fulfilling prophecy where “Big Wine” producers who have the distribution muscle to be widely available are rewarded with top rankings that further cement their market dominance and so-called “premium” status.

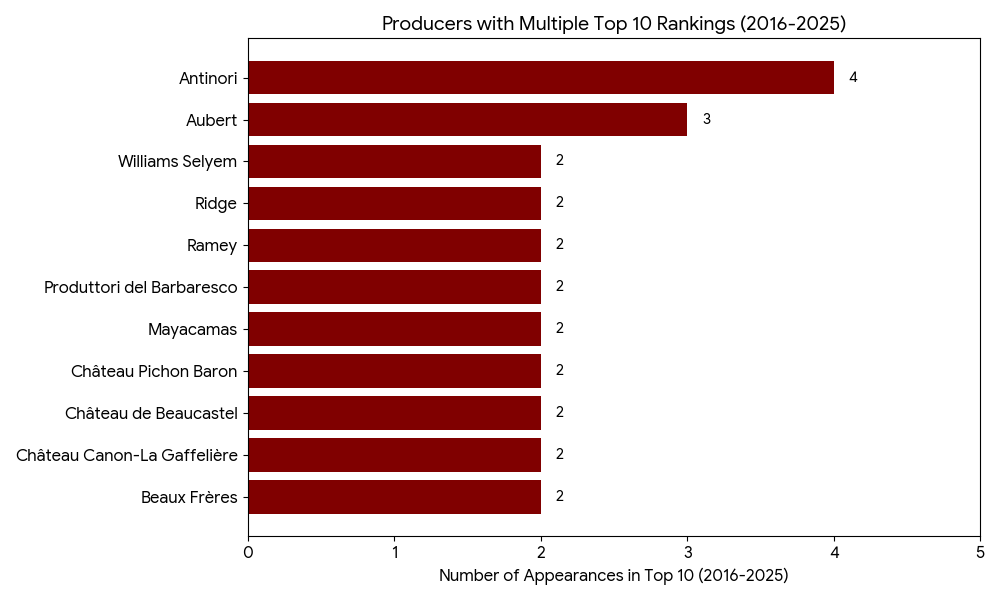

On top of that, the prominence of a few specific producers (most notably Antinori & Aubert) highlights a preference for consistency and historical pedigree over “new discovery” and highlighting under-appreciated and overlooked quality wine regions. The fact that a handful of estates can secure multiple Top 10 spots in a single decade suggests that once a producer aligns with the Wine Spectator credo, they become “safe bets” for the editorial team. While academic studies find only marginal evidence of direct “pay-for-play” regarding advertising, the alignment between major advertisers and the regions featured in the list is hard to ignore. For the average reader, the list appears to be a comprehensive survey of the world’s best wine, but in reality is more of a high-level shopping guide for the “usual suspects” of the luxury wine market.

Perspectives “we” can take on this:

Cynic: It’s a marketing engine that rewards big advertisers and promotes high-volume brands to keep the industry’s “big players” happy (UNLIKE ME!).

Pragmatist: It’s a reflection of the U.S. market. The biggest, most consistent producers in the best regions “naturally” rise to the top of a list that demands high volume. (DUBIOUS!)

Purist: The list is mathematically flawed because it weighs “availability” as heavily as “quality,” meaning it isn’t a list of the best wines, but the most popular and widely distributed “highly scoring” wines. This severely penalizes the poor little “small producers” making their merry little way in the “premium wine world” and keeps the “big boys” (e.g. Antinori) dominating the annual lists FOREVER.

A Little ”Taste Test”

We decided to taste one of the wines from the list (a Barbaresco from the exceptional producer Produttori, WS#7 of 2025) and pit it against a wildcard wine from India, an afterthought of a country in the world of zeus juice. The Produttori is shown as having a price of $57 on the Wine Spectator list, making it the second cheapest to the #3 wine Ridge Lytton Springs (though it is actually the cheapest wine on the list according to Wine Searcher). Even still, it represents a wine that is probably too expensive for the lay-drinker.

By volume the Indian wine is between 1/2 and 2/3 the price, and we chose it randomly without having ever tasted it before (because “why not?”). The question we’re asking is – is the extra money worth it for a “top 10” ranked wine (even the cheapest one available), and was India (and everywhere else that isn’t France or the US) basically snubbed this year?

2012 Krsma Estates Cabernet Sauvignon 1.5 L / $60

Profile: Black plum, prune, mint, blueberry, licorice, bay leaf, sassafras, chocolate, tobacco

Palate: Dry, medium+ tannin, medium+ acid, full body, long finishTook a real gamble on this “South Indian beauty” and it “paid off.” It was amazingly fresh for its “age” and showed lots of layers that just kept “paying off” as the sun made its merry little way through the sky. Incredible value from an incredibly underrated region of the so-called “world.”

Score breakdown: Balance 37 / Aroma/Flavor 17 / Concentration 15 / Length 15 / Complexity 8 = 92 points (Z)

2021 Produttori di Barbaresco (#7 WS wine of the 2025) / $51

Profile: Rose petals, violets, red cherry, dried strawberry, cranberry, blackberry, licorice, ginger root, sassafras, sandalwood, chocolate, white pepper

Palate: Dry, high tannin, medium+ acid, full body, long finishClassic, great quality Barbaresco. Absolutely worthy of the list, and not at all unexpected, because as “we” know, Produttori di Barbaresco is consistently an outstanding value nebbiolo that often performs above its “proverbial” weight. The 2021 is in another league with impeccable balance, pronounced floral notes, a mix of fresh and dried red and black fruit character and perfectly integrated oak spice.

Score breakdown: Balance 40 / Aroma/Flavor 18 / Concentration 15 / Length 15 / Complexity 8 = 96 points (Z)

So what does this little sample size of one tell us? Well, it tells us at very least that the list contains some quality wine, but it’s also meant to highlight that top notch wines can be found in a far broader spectrum of regions and styles than what the Wine Spectator likes to pleasure themselves with.

But it’s not a question of whether or not the wines that do make the list are worthy of praise and/or your time. What we hope to highlight here today is that the Wine Spectator’s Top 10 list is created by looking through an extremely narrow window and it does a disservice to the incredible diversity of wines out there that never had a shot of being showcased in the first place — even within the confines of the selection criteria (which are questionably applied).

Ultimately, it’s just a list of pricey wines that Wine Spectator felt like promoting.

Disagree? Dox us and send us hate mail. Or complain in the comments.

Until next time, HAPPY DRINKING PEOPLE.

Cheers!

Isaac & Zach

Hopefully, I won't stay up too late tonight noodling on this data...but I will.

The red wine stat, 82% was what stuck out to me the most. The second has to be the three main players of Napa, Italy, France, with Australia and Spain barely ever cracking through. I get all the criteria WS lists as cover, fine, whatever.

Third: Points inflation. So many wines now get 90+ points, they could pick a Lodi or Paso wine for that fact with the "X-Factor" wildcard. They could pick any wine, anywhere in the world that has some basic distribution here in the States. But as you rightly point out, Aubert isn't just sitting on a shelf somewhere. Selyem isn't quite has difficult to obtain, unless it was from a specific vineyard. So why can't a Pinot from the Central Otago crack the Top 10? Or a killer Malbec blend from Argentina?

I like the data driven approach to what you're doing.

Wooo, someone had a BEE in their bonnet on this topic! LOOK at those pie charts you whipped up! Putting in the WORK, brothers!

I had to vote "Other" in the poll, because it's "All of the Above", imo. I rarely read anything from major wine publications for this very reason. There are too many conflicts of interest when they're that big, that in need of money and eyeballs and support. And they'll always be behind every actually important curve, jumping on trains, never getting them rolling.

That said, super surprised a 2012 Magnum Indian wine did that well! I adore under-tasted territories like that but even I was like "Good god, are you setting it up to fail?!?" And then it tasted great, thank goodness. Bravo, guys, great post.